If Newton's apple had fallen beside a fermentaer, he might have wondered: How can a few liters of fragrant liquid yield such disappointing results when scaled up?

When scaling up fermentation processes from laboratory batches of a few liters to industrial production of hundreds or even thousands of liters, what appears to be a simple volume increase actually conceals a series of complex engineering challenges and ingenuity.

Fermentation is a core process in the modern biotechnology industry. Whether in food brewing, pharmaceutical development, or bioenergy production, the performance of fermenters as foundational equipment directly impacts product quality, efficiency, and cost. Process-level customization of stainless steel fermentors has emerged as a solution precisely in this context.

When scaling up fermentation processes from laboratory batches of a few liters to industrial production of hundreds or even thousands of liters, what appears to be a simple volume increase actually conceals a series of complex engineering challenges and ingenuity.

Fermentation is a core process in the modern biotechnology industry. Whether in food brewing, pharmaceutical development, or bioenergy production, the performance of fermenters as foundational equipment directly impacts product quality, efficiency, and cost. Process-level customization of stainless steel fermentors has emerged as a solution precisely in this context.

-

Scaling up is not copying

Different industries have varying requirements for fermenters. The food industry prioritizes hygiene, safety, and large-scale production; the pharmaceutical industry demands sterile control and process stability; while the biofuel industry focuses more on efficient conversion and cost control.

Scaling up is never a simple matter of proportional replication. The same microbial strain often exhibits different behaviors under small-scale, pilot-scale, and production-scale conditions. Success at the small-scale level is merely the beginning of the story. The pilot-scale stage represents a major leap from technical feasibility to engineering stability—and it is also the most prone to failure. This phase faces three prominent challenges.

1. The Conflict Between Process Consistency and Scale

During pilot-scale testing, agitator blades can easily shear liquids into uniform flows. However, in large vessels, fluid paths lengthen and shear forces become unevenly distributed, readily forming dead zones or short circuits. Microorganisms dwelling too long in these areas may deviate from expected metabolic pathways, altering product composition. Additionally, the oxygen transfer coefficient (kLa) exhibits nonlinear decay with increasing volume. In large-scale fermentation, oxygen transfer becomes the bottleneck. These nonlinear effects render the “optimal parameters” from small-scale trials directly ineffective in large volumes.

Scaling up is never a simple matter of proportional replication. The same microbial strain often exhibits different behaviors under small-scale, pilot-scale, and production-scale conditions. Success at the small-scale level is merely the beginning of the story. The pilot-scale stage represents a major leap from technical feasibility to engineering stability—and it is also the most prone to failure. This phase faces three prominent challenges.

1. The Conflict Between Process Consistency and Scale

During pilot-scale testing, agitator blades can easily shear liquids into uniform flows. However, in large vessels, fluid paths lengthen and shear forces become unevenly distributed, readily forming dead zones or short circuits. Microorganisms dwelling too long in these areas may deviate from expected metabolic pathways, altering product composition. Additionally, the oxygen transfer coefficient (kLa) exhibits nonlinear decay with increasing volume. In large-scale fermentation, oxygen transfer becomes the bottleneck. These nonlinear effects render the “optimal parameters” from small-scale trials directly ineffective in large volumes.

2. The Conflict Between Data Value and System Complexity

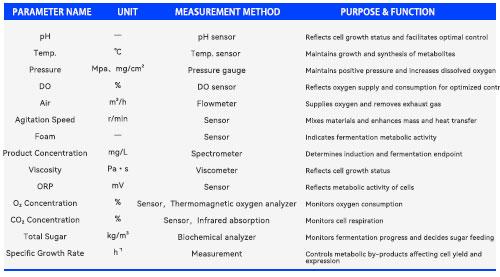

Pilot-scale testing serves as a valuable window for obtaining critical engineering data. While small-scale systems offer rapid response and minimal control lag, traditional pilot-scale equipment often features rudimentary control systems and fragmented data chains, making it difficult to capture high-fidelity, interconnected process parameters. Beyond conventional metrics like temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen, these parameters should include agitation power, aeration load, control response lag time, and the coupling relationships between key variables. The absence of such data during pilot testing directly compromises fermentation stability and reproducibility, necessitating costly revalidation during production.

Pilot-scale testing serves as a valuable window for obtaining critical engineering data. While small-scale systems offer rapid response and minimal control lag, traditional pilot-scale equipment often features rudimentary control systems and fragmented data chains, making it difficult to capture high-fidelity, interconnected process parameters. Beyond conventional metrics like temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen, these parameters should include agitation power, aeration load, control response lag time, and the coupling relationships between key variables. The absence of such data during pilot testing directly compromises fermentation stability and reproducibility, necessitating costly revalidation during production.

3. The Conflict Between Compliance Verification and Cost Efficiency

For industries such as pharmaceuticals and food processing, pilot-scale testing serves as a critical step in process validation and regulatory documentation. Equipment must comply with GMP and other regulations regarding materials, cleanliness, and data integrity. Traditional custom manufacturing models often involve lengthy lead times and high costs, making it difficult to respond swiftly to the pace of R&D.

Faced with these challenges, off-the-shelf equipment often falls short. Custom-designed fermenters can optimize mass transfer efficiency, mitigate contamination risks, and enhance process consistency tailored to the specific requirements of different industries—this is precisely where their core value lies.

For industries such as pharmaceuticals and food processing, pilot-scale testing serves as a critical step in process validation and regulatory documentation. Equipment must comply with GMP and other regulations regarding materials, cleanliness, and data integrity. Traditional custom manufacturing models often involve lengthy lead times and high costs, making it difficult to respond swiftly to the pace of R&D.

Faced with these challenges, off-the-shelf equipment often falls short. Custom-designed fermenters can optimize mass transfer efficiency, mitigate contamination risks, and enhance process consistency tailored to the specific requirements of different industries—this is precisely where their core value lies.

-

HOLVES Fermentation Solutions

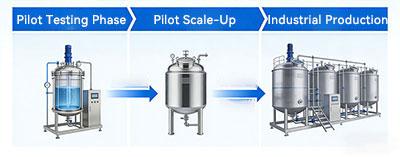

To address these challenges, a systematic, phased customization and upgrade strategy is essential. Taking HOLVES Su310 series of intelligent stainless steel fermenters as an example, their modular design and intelligent control systems enable a seamless transition from laboratory-scale to industrial production.

1. Pilot Testing Phase: The Su310 series focuses on experimental flexibility and precise data acquisition. Featuring servo motor drive, its compact structure ensures smooth, accurate operation and easy maintenance. The integrated touchscreen control system enables real-time monitoring of critical parameters such as temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen(DO), while supporting data export for analysis.

2. Pilot Scale-Up: During the pilot stage, the Su310 series is equipped with automated functions such as automatic sterilization and automatic lid lifting, minimizing manual intervention. The tank's height-to-diameter ratio is adjustable, supporting interchangeable agitator types to accommodate various fluid characteristics. The multi-tank parallel design further enables parallel testing, accelerating process optimization.

3. Industrial Production: For the production phase, the Su310 series enables centralized monitoring and intelligent scheduling of multiple fermentors. Efficient air filtration and CIP systems ensure maximum sterility and operational efficiency for large-scale fermentation. Next-generation systems like HF-Control V3.0 support holographic smart control and multi-level permission management, featuring electronic signatures, audit trails, and one-click export capabilities. This ensures traceable operations and peace of mind.

2. Pilot Scale-Up: During the pilot stage, the Su310 series is equipped with automated functions such as automatic sterilization and automatic lid lifting, minimizing manual intervention. The tank's height-to-diameter ratio is adjustable, supporting interchangeable agitator types to accommodate various fluid characteristics. The multi-tank parallel design further enables parallel testing, accelerating process optimization.

3. Industrial Production: For the production phase, the Su310 series enables centralized monitoring and intelligent scheduling of multiple fermentors. Efficient air filtration and CIP systems ensure maximum sterility and operational efficiency for large-scale fermentation. Next-generation systems like HF-Control V3.0 support holographic smart control and multi-level permission management, featuring electronic signatures, audit trails, and one-click export capabilities. This ensures traceable operations and peace of mind.

This phased customization strategy ensures consistency in fermentation process parameters during scale-up, reducing uncertainties and failure risks in the scaling-up process.

The scale-up of stainless steel fermenters should not rely excessively on individual engineers' experience, but rather become a repeatable, auditable, and compliant standard process. When pilot-scale data can be directly accepted by regulators, and when the cost curve of small-scale production is clearly understood, scale-up ceases to be a perilous leap and instead becomes a predictable step.

The scale-up of stainless steel fermenters should not rely excessively on individual engineers' experience, but rather become a repeatable, auditable, and compliant standard process. When pilot-scale data can be directly accepted by regulators, and when the cost curve of small-scale production is clearly understood, scale-up ceases to be a perilous leap and instead becomes a predictable step.